Analysis | June 2023

The Security Playbook

Analysis | June 2023

This paper sets out the ‘Security Playbook’ – Civic Futures’ shorthand for the expansion and abuse of security powers, tools, and discourse by States in ways that criminalise and restrict activists – and introduces the ways in which philanthropy can support civil society to disrupt, reform and transform this trend.

The Security Playbook is set to be the dominant driver of closing civic space this decade and work to counter it offers the best opportunity for philanthropy to challenge attacks on democracy and rights, and to build toward a civic future.

As movements think up radical new ways of organising our societies, politics and economic lives, states and non-state actors are finding novel ways to repress them – to ‘close’ their civic space in service of existing political and economic power by subjecting them to repression that increasingly uses national security as a justification and a tool.[1] It threatens every sector and every issue – from climate justice to the rights of racial, ethnic, religious minorities, refugees and migrants, women and LGBTQI+ peoples, to economic justice and public health. COVID-19 has accelerated these trends.

In 2019 the Funders Initiative for Civil Society (FICS) carried out research [2] investigating the underlying drivers behind the phenomenon of closing civic space. What emerged were three clear global trends that were contributing to closing space:

Our analysis shows that the expansion and abuse of state security powers, tools, and discourse – which we’ve termed the ‘Security Playbook’ – is being rolled out with extraordinary momentum and will be the dominant driver shrinking civic space over the next decade but is particularly neglected.

The Security Playbook is the set of tactics misused or abused by states around the world with the outcome that civic space and democracy is limited under the aegis of security. Understanding this Playbook, where it comes from, and how it is used, is essential if we are to counter it.

‘Closing civic space’ may well describe age-old political repression, with its origins in the philosophical foundation of the state and the relationship between the state and citizens, but the coming together of the Security Playbook is driving a step change in this phenomenon: dramatically impacting the scale of repression and tipping the balance in favour of the state and vested interests. To date, funders have not adequately prioritised this threat – and, as a result, civil society has not developed its capacity to track and counter the proliferation of security and counter-terrorism laws and technologies, nor build the collective narrative power to counter the fear-based discourse that normalises their abuse.

Closing space does not affect everyone equally. Civic space can be experienced differently by individuals in the same location; security powers have a disproportionate impact on racialized minorities and economically disadvantaged groups. We also know that changes in civic space are not uniform or linear; as one state cracks down on protest or introduces a new foreign funding law, somewhere else civic movements burst open new spaces for discussion and debate. [3]

When we understand that we are talking about power, a different story emerges, revealing the ways in which power shifts and flows. We notice how people find ways to take back power and can think more clearly about how to support them. Rather than a linear narrative of closing space, which feels inevitable, all-encompassing, and impossible to fight, a dynamic story emerges of opening and closing spaces for people to express themselves, gather and organise to participate in social, political and economic life.

The Security Playbook does not emerge at the state level from a vacuum – a diverse security ecosystem made up of public and private actors sustains and benefits from the security paradigm. A growing and opaque transnational security architecture – a web of UN and international bodies responsible for setting frameworks and standards on counterterrorism, violent extremism and national security – equip states and corporate actors with the power to restrict civic space at the national level.

The defence, security, and technology industry benefits when governments use the Security Playbook to respond to political or social problems. The technology industry is slowly becoming intertwined with all aspects of governmental service delivery, with concerning synergy between state power and corporate surveillance capitalism. These actions are justified and made ‘common sense’ through public and corporately owned media. Social media platforms thrive on fear-based narratives. Media outlets that are captured by the state or in hock to corporate interests are more likely to espouse hard security discourse and influence the public and policymakers to support the Security Playbook or the decision-makers who utilize or benefit from its approaches.

I heard Patrisse Cullors from the Black Lives Matter Global Network say a while ago that somebody had to actually first imagine prisons and the police themselves in order to create them. […] I also think that once things are actualized into the world and exist, you can’t imagine how the world functioned before it.

– Tawana Petty. Safety vs Security: Are you safe or are you secure? Open Data Bodies, 2019. [4]

The Security Playbook is set to be the dominant driver of closing civic space this decade. Yet the field of actors working to counter the Playbook is small, fragmented, and massively underfunded. Working to disrupt, reform and transform this Playbook offers the best opportunity for philanthropy to effectively counter attacks on democracy and rights.

FICS’ 2020 paper, Rethinking Civic Space, looked at what populist and anti-rights movements were doing around the world to draw lessons and understand what we are up against.[5] Overwhelmingly, the research identified that these movements were investing in ideas, value-based narratives and the means of production of culture – including takeover of media, disinformation, control of internet. They were investing in transnational movements in addition to foresight and strategy.

In contrast, most of the work supporting rights-based movements is defensive in nature. Independent philanthropy has long organised to counter the harms that result from closing civic space, whether through resourcing pushback against stricter protest laws or administrative harassment, or by supporting the protection of activists facing slander, arrest or violence. This work is of course vital – without this work civil society will not have the space and safety to engage with proactive strategies – but for movements advocating for alternative, rights-based ideas on how we organise society, political life, and the economy to take advantage of this rare moment of opportunity we must do more.

The lesson from populist and anti-rights actors is clear: we need to drastically step up our work at the transformative level and resource narratives, movement-building and culture change. So far, philanthropy’s support for work at this level has been weak.

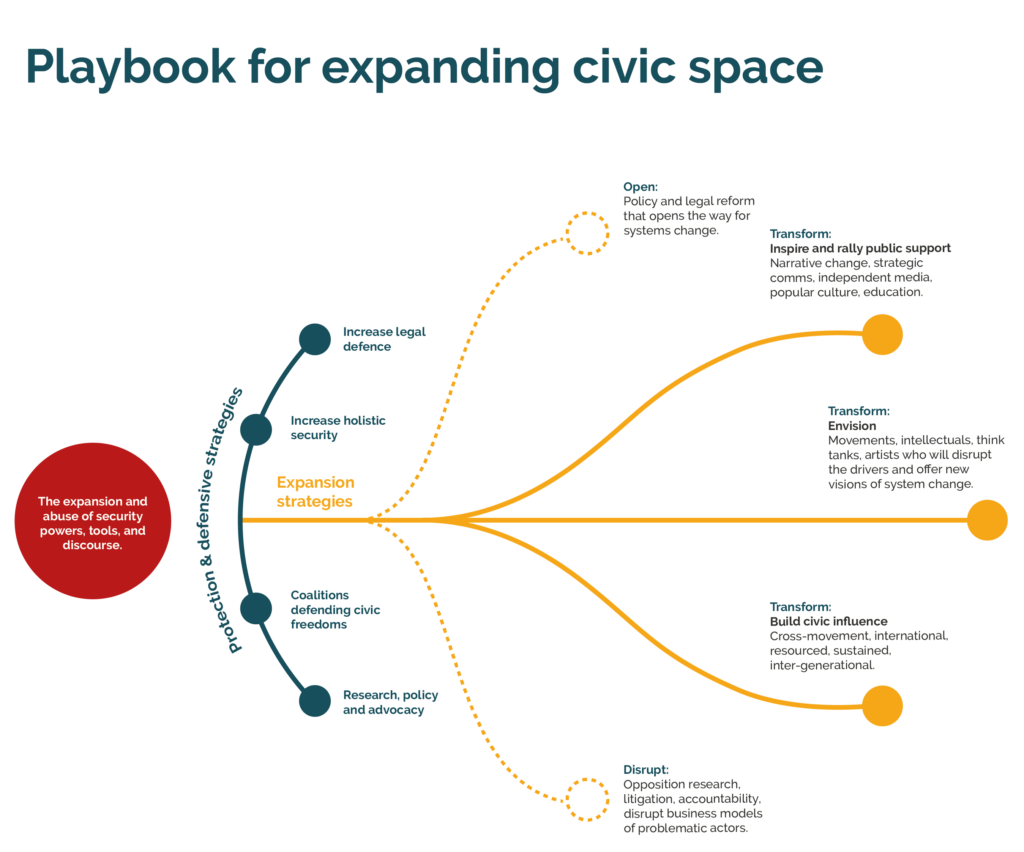

The following visual sets out a playbook to disrupt, reform and transform the Security Playbook and offers the funder community a tool to map the strategies we are already supporting, identify opportunities to share and align our work, and identify where there are critical gaps where funders could make a real difference.

Over the last two decades the convergence of different drivers has created a conducive environment for States to restrict civic space in the name of safeguarding security.

Disruptive strategies seek to:

Disruptive strategies can create openings to engage with States, international policymakers and corporations on policy and legal reforms.

Reform strategies seek to reverse the tide of restrictive measures stemming from national and transnational security bodies to secure accountability and open the space for reform including greater democratic oversight of security bodies and laws and their impact on civic freedoms.

Reform strategies seek to:

Current approaches to security have failed to make the world more stable and safer and are also not fit to address the greatest drivers of human security in the next decade; the effects of climate change, the increased chance of pandemics, and economic fragility. In this context it is increasingly hard to argue that terrorism is the primary threat to public or national security. Transformative approaches build the alternatives to the hard security paradigm.

Transformative strategies seek to:

In the years since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 (9/11), most states have gained extensive powers with the stated aim of combating ‘terrorist’ and ‘extremist’ groups.[6] Security focused frameworks, policies and measures dovetail with hard security laws. Many states have misused or abused the powers they have gained, restricting civic space and infringing human rights and democracy.[7]

The targeting of civil society is not a random or incidental aspect of counterterrorism practice. [data] suggests the hard-wiring of misuse into counter-terrorism measures taken by States around the globe.

– Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, UNSR on Protection and Promotion of Human Rights while Countering Terrorism [8]

An opaque and growing transnational security architecture of 38 UN agencies, and over 200 transnational and regional bodies, set counterterrorism, extremism and national security frameworks and standards globally.[9] Once a check on state infringements of human rights, the UN, which leads the transnational security architecture, has done little to prevent these far-reaching counter terrorism and security laws and norms being used to restrict civic freedoms. Indeed, many of the counterterrorism and security laws and policies used to close civic space for progressive movements originate or have been legitimised, promoted, and consolidated by this architecture.

The security frameworks promoted by the transnational security architecture possess two key features that run contrary to traditional notions of due process and make them perfect tools for misapplication or abuse.

Just as almost any person can be deemed as a security threat, almost any issue can be reframed as one of national security. This has led to more and more national and transnational public policy issues being reframed as issues of national security requiring ‘security’ responses. Civil society actors working on, for example, immigration and border control, international development and humanitarian responses, have faced an increasingly hostile and challenging environment.[10]

The most well-documented direct negative impact on civil society is the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). The FATF is mandated to combat money laundering and the financing of terrorism through the issuing of recommendations to states with financial incentives and disincentives. Its recommendation 8 notoriously stated that civil society organisations were “particularly vulnerable” to terrorist abuse, which in some cases directly led to, and in others justified and legitimised waves of laws restricting the cross-border funding of CSOs over the last fifteen years. Successful international civil society advocacy with the FATF led to the revision of recommendation 8 in 2016.[11]

The complexity, opacity and sheer volume of bodies and agencies engaging in counterterrorism means that there are other agencies – in particular those with a mandate on cyber security, content moderation, cross-border funding and telecommunications – carrying out work with a similar direct negative impact on civil society. FICS has commissioned new empirical research from Statewatch, a respected think tank producing critical research, policy analysis and investigative journalism on civil liberties, to identify entry points for targeted advocacy.

Despite the growing impact of security frameworks on a wide range of human rights issues, since the winding down of work that sought to address the post 9/11 ‘war on terror’ this has not been viewed as a priority by funders. As a result, civil society has limited capacity to track and counter the proliferation of counter terrorism and security laws and discourse globally.

Most civil society focus is understandably on mitigating downstream impacts rather than tackling the upstream transnational project that drives the proliferation of laws. Until very recently there has been little to no scrutiny of the human rights impacts of the norms being set by transnational security bodies. Only a small number of peace and security and human rights funders support the work of coalitions seeking to address the issue. The outcome is that civil society is often not present in key spaces where the future of civic space is being shaped.

There are some emerging groups and networks generating a strong collective critique[12], and growing clarity on advocacy targets – including, at transnational level, the CSO Coalition on Human Rights and Counter Terrorism and Charity and Security Network and, at national level, groups like Nigeria’s Action Group on Free Civic Space led by Spaces for Change. These groups need support to grow their work. Apart from the organisations holding the secretariat function, very few have dedicated funding to cover the substantial contributions made to advocacy in relation to counter-terrorism frameworks. The core contributing members need funding to support their coalition work, while new members, frequently coming from global majority countries need support to develop dedicated counter-terrorism programmes.

The development of technologies such as smart phones with cameras enabled the documenting and exposure of human rights violations, and the popularisation of social media platforms enabled mass organising of protests and revolutions, such as the Arab Spring. But while technology has provided tools for recording and documenting human rights violations, and opened spaces for civic organising, in response, governments have found novel ways to close those online spaces and repress organising.

“Often, for undocumented, Black communities and other marginalized communities, the more secure a city proposes to be, the less safe those communities become.”

Tawana Petty, ‘Safety Vs Security: Are you safe or are you secure?’ [13]

Thanks to the disruptive work of researchers, journalists and NGOs, there is increased awareness in civil society and the philanthropic community of the existence of powerful spyware such as Pegasus, being used to track and follow activists. These technologies invade the privacy of activists and their families, providing the authorities with information which can be twisted to smear them in the public eye, or be used in trumped-up criminal cases against them.

Beyond the targeting of individuals, society at large is becoming accustomed to daily surveillance. With the use of biometrics and facial recognition technologies in public and private spaces, ‘smart cities’ are increasingly becoming a part of our day-to-day lives, with security rhetoric frequently the justification. The negative impact of these technologies is not always immediately apparent, and the convenience and practicality can be alluring. However, critics argue that the technology itself does not function as well as the companies would have us believe, but rather serve as a form of “security theatre”, maintaining public confidence through a “visual and dramatic perception of security”.[14] Not only do they not function as they are purported to, but also reproduce and reinforce racism, for example, facial recognition technology has been shown in the US to misidentify black men.[15]

Large tech platforms and telecoms companies are also increasingly pro-active – or legally obliged – to police their users’ activities for “security threats”: on social media platforms or telecommunications networks more broadly; in the international banking and travel systems; and in the protection of the “critical infrastructure” that is often the target of protest or dissent. Lawful access regimes require companies to retain key data and cooperate with states in the surveillance of targeted groups and individuals. These regimes often provide a gateway for States to target civil society organising online; identify activists and protestors from mobile phone records and geolocation data; and monitor and obstruct the funding of CSOs.

Both targeted and mass surveillance create a chilling effect, raising the level of risk for anyone engaged in challenging power. Enormous time, energy and resources are taken away from activism and social change and directed towards self-defence.

“A small number of extremely powerful firms, namely Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, have what the European regulators call gatekeeper power – the right to decide who can speak, who can reach one another”

Cory Doctorow, technology activist, writer, and journalist [16]

Despite being such an essential site for civic space, the internet is increasingly controlled by a small number of large companies, who by controlling the public space for conversation, exert enormous influence over the functioning of democracies and hold the key to the last remaining sites for free expression in authoritarian states.

Power dynamics and inequalities are played out in the context of content moderation, with civil society highlighting over-moderation of some content (i.e. a lack of nuance in moderation of Arabic language content, with the over removal of content perceived to be supporting terrorism[17]) and under-moderation in other contexts, such as hate speech directed towards minority populations – in the worst cases ethnic cleansing was preceded by online hate campaigns.[18]

In countries where traditional media is under heavy government control, technology companies are vulnerable to legal pressure. States pressure companies to impose censorship on dissidents, by removing social media accounts, blocking critical content or shutting down online or offline protest through internet shutdowns or throttling.[19]

New regulations being introduced around the world have so far failed to address these problems and instead seek to regulate ‘harmful content’. New laws range from imperfect to brazenly dystopian regulation seeking to blackmail social media companies into imposing government censorship.[20]

Bloated national security budgets and taxpayer subsidies for security research and development have created a huge global marketplace for companies selling technological solutions to crime, terrorism and political risks – including the risk of social unrest.

The revenues on offer have tempted many large technology companies into the sector. National security drives the development of new technologies, with heavy investment from state defence institutions in Big Tech for the development of sophisticated surveillance tools to gather enormous amounts of data and the artificial intelligence required to analyse and make sense of it. This helps drive the current monopoly of a handful of companies.

There is a revolving door between government and leading security companies. Public-private partnerships are widespread and subject to little scrutiny or accountability, while private actors increasingly engage with government counterparts on international norm-setting on counterterrorism, security and surveillance.

There is a significant export market for surveillance and spyware tools, with the predictable consequence of tools made in one context coming to be used to target dissidents, activists, and social movements in other regions and countries. Efforts to regulate sale and export have been insufficient.[21] Export controls can be circumvented by multinational supply chains, and States with large or growing security industries (including China, Israel and now the UAE) don’t participate.

Civil society organisations working in these spaces have consistently highlighted and problematised these issues but have not yet been able to build civic power to effect transformation. As the pace of technological change intensifies, this tactic of the Playbook requires an urgent step-change in investment to connect related fields of civil society actors and develop new analysis to inform effective strategy. This section offers a snapshot of some of key implicated fields.

Growing critique on the uses of spyware, biometrics, and facial recognition technology has led to new efforts at regional and national levels to advocate for appropriate regulation and restrictions on the most invasive types of technology.[22] There is work attempting to disrupt the spyware industry through investigating and exposing its use against civil society. However, the forensic technical expertise required is rare; it sits mainly in a very few global north-based organisations (incl. Amnesty Tech, Citizen Lab, AccessNow), many of whom are engaging in important work to train and build local expertise – but this is intensive, time consuming, and massively underfunded.

There is a lack of consensus on how to deal with issues of censorship and content regulation, with divides between those who support more regulation, those who oppose regulation because of broader consequences on the right to free expression, and those who advocate different kinds of regulation (i.e., using competition law to break up monopolies rather than regulating the speech itself). This is an emerging space for debate, and it will be important for funders to ensure that the space is kept open for a range of civil society voices.

The speed of development of AI technologies has left civil society without a clear strategy on how to approach the potential harms on civic space.[23] As the industry engages in an arms race to release the latest tech, parts of civil society are being supported to build expertise but there is yet to be a coordinated, coherent position and ask. Technical experts, even where they have undertaken impressive work on policy advocacy (for example within the EU), largely lack the communications skills to capitalise on sudden public awareness of AI in the wake of new tools like ChatGPT.

A small number of actors are working to move beyond defensive and digital security approaches to focus upstream. Efforts to disrupt the surveillance capitalist business model are supported by funders including Luminate, Mozilla, and Ford Foundation, but we have not encountered a widespread or coordinated civil society strategy to disrupt the revolving door between national security agencies and Big Tech. Very few civil society organisations have the expertise and knowledge to engage with technical norm-setting bodies; those that do (e.g. ARTICLE 19) are stretched thin, which means that in many instances norms are being set without any input from civil society.

With the exception of spyware and biometric technology, which is usually understood in the context of national security discourses, the discussions on content, AI and infrastructure usually touch on national security but don’t apply a security lens to the work as a whole. A few thought leaders point to the nexus between the tech industry and security agencies, but there remains no coordinated strategy to push back.

Underpinning the Security Playbook is a potent narrative: threats facing us are so severe and those who may threaten us are so many and so unpredictable, that only hard security measures can keep us safe – even at the expense of human rights and civic space.

Threat-based concerns are leveraged by actors with competition-based and scarcity-based narratives that serve both distinct and overlapping agendas. The actors include populists, politicians, illiberal conservatives and far-right groups and private sector interests.

In practice, this looks like smear attacks against activists, journalists and human rights defenders as supporting or promoting terrorism or protesters as a threat to the peace, where protests and movements are called ‘insurrection’.

Hard security narratives aren’t limited to those autocratic regimes using the spectre of real or manufactured threats to justify intrusive surveillance and restrictive laws to quash criticism. Populists in semi-authoritarian and democratic states, emboldened by support from ethno-nationalist, far right and religious conservative groups, market a nativist patriarchal version of social, cultural and economic security by ‘othering’ minorities and fearmongering of ‘outsiders’, as threats to health, security, access to public services, jobs, prosperity and “traditional” values. This squeezes the safe space for marginalised communities, building public support for restrictions on the rights of these groups and the civil society groups that work with them (see: Poland, India, Brazil, the Philippines)

In liberal democracies, politicians across the mainstream political spectrum craft the expansion of security powers and expenditure as ‘pragmatic’ and ‘patriotic’ while depicting civil society advocates for alternative security models as naïve and wilfully placing national security at risk (see: the UK, France, the US). Socially conservative and far right groups, ethno-nationalists and religious fundamentalists, and some corporate actors, collude or concur with this security discourse as they reap its benefits.

“To the FBI of the 1920s, immigrant Jews were agents of anarchist and communist subversion; to the FBI of the 1960s, Black liberation was a hidden communist plot; to the FBI of the 2000s, Muslim political association was a precursor to terrorism.”

Arun Kundnani, Abolish National Security [24]

Coercive state power has always been used at the service of racial hierarchies. Counterterrorism policies have frequently led to the stigmatisation of entire communities: the anti-Muslim rhetoric which was engendered by the War on Terror is still with us and has “enabled distinctive incarnations of anti-Muslim racism to appear in Myanmar, Thailand, Sri Lanka, and India, where Muslims have been scapegoated for the spread of COVID-19″.[25] Fears around immigration and non-dominant identity groups (including non-dominant gender identities[26]) have been successfully mobilised and used to justify securitisation.

Reframing policies to avoid mentioning particular religious, racialised or otherwise minoritized groups does not solve the problem. Genuine solutions require a clear-eyed focus on dismantling these structures of oppression. At its core the phenomenon of closing civic space is the manifestation of the competition between the dominant hard security discourse – employed in service of dominant powerful hierarchies of race, class, and gender – and rights-based movements, with alternative, rights-based visions of how to organise society, political life and the economy.

At the civil society level funders have often shown a discomfort acting in the realm of ideology and worldview, seeing it as too ‘political’. Investment in technocratic fixes of communications training and consultancies results in a piecemeal, reactive approach. Short term communications campaigns – ‘Journalists are not terrorists’, etc – often counter-productively amplify the negative association. Documenting abuses and name-and-shame tactics don’t win the hearts and minds of most policy makers and the public. Niche campaigns promoting the positive contribution of civil society fail to cut through the noise. The influence of the dominant security discourse in underwriting the Security Playbook is unaffected.

There is a small but growing field of initiatives and communities pursuing cultural capital, narrative-building, and strategic communications approaches, but this ecosystem is fragmented and disconnects can undermine common work and effective sharing of learning.[27] Peace and security actors and communities affected by conflict and the war on terror have sought for many years to challenge and develop alternative policy frameworks rooted in human rights, peace and feminism, but resources are scant. Explicit work to cultivate public and political support for these alternatives is not well-connected with the wider narratives field; further investment is needed to ensure these actors can benefit from growing expertise among wider civil society.

A handful of movements have developed communications to address the impact of security on civic space, especially concerning state security and police violence in the context of struggles against racial injustice, climate change, corruption and poor governance (e.g., Movement for Black Lives; Extinction Rebellion; #EndSARS; Milk Tea Alliance), exposing the way the security architecture impedes freedom of assembly and expression, especially through mass protest. Lessons from this work should be amplified and resource provided to step up activity where effective.

Independent media with a rights-leaning outlook is often attacked by states and other actors looking to uphold the status quo. As with all outlets they have had revenue streams decimated by tech platforms, limiting their ability to do quality reporting, inform the public, and hold accountable the companies and governments benefiting from the Security Playbook. Furthermore, security matters such as digital surveillance are complex and most journalists do not have the expertise or resources to investigate these effectively. A few actors are leveraging advertising revenue and ethical principles in journalism to defund hate-fuelling media outlets. More opportunities are needed for funders working to support movements most impacted by the Security Playbook to come together with funders who have expertise in supporting independent media in creative ways.

Civic Futures is a major philanthropic initiative working to tackle the Security Playbook at scale.

This moment presents an unprecedented opportunity for funders seeking to strengthen civic freedoms to come together with those who support the movements most impacted by criminalisation, surveillance, and harassment, to begin to identify a vision for a future unhindered by the Security Playbook and a roadmap for realising this.

For more information about what it means to get involved in Civic Futures, get in touch.

The power of civil society to counter the security playbook and open civic space lies in movements joining forces to develop strategy and learn around what works.

Civic Futures seeks to support the existing groups that work on these issues and fund those affected by this trend but new to the work. This draft strategic framework builds on the learning and thought leadership of a group of experts and funders that have led and sustained this work over the last two decades. We would like to thank:

Colleagues from the European Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ECNL), the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL), Human Security Collective (HSC), Saferworld and the Security Policy Alternatives Network (SPAN), Rights and Security International and Open Society Foundations who have provided generous input and feedback.

Fionnuala Ni Aoilain (the former UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism) and Ben Hayes from AWO for their research and deep technical expertise.

The Fund for Global Human Rights is a founding partner of Civic Futures and the first funder to align significant programming behind its analysis. The Fund’s Enabling Environment for Human Rights Defenders Program has contributed its extensive experience of supporting grassroots movements and activists that bear the brunt of closing civic space and its thought-leadership on narrative change to shape this framework. The Fund is a valued first partner in Civic Futures and we invite others to join us to shape and realise our collective vision.

No one sector can disrupt, reform and transform the security playbook alone: we must work together to refine this framework as a collective resource and to build an eco-system that strengthens civil society’s capacity and expands civic space.

[1] Dr Anne Charbord & Prof Fionnuala Ní Aoláin. The Role of Measures to Address Terrorism and Violent Extremism on Closing Space. University of Minnesota, 2019.

[2] Ben Hayes & Poonam Joshi. Rethinking civic space in an age of intersectional crises: a briefing for funders. Funders Initiative for Civil Society, 2020.

[3] For a more detailed exploration of these issues, see: Feminist Resistance and Resilience: Reflections on Closing Civic Space. Urgent Action Fund Sister Funds

[4] Tawana Petty. Safety vs Security: Are you safe or are you secure? Open Data Bodies, 2019.

[5] Ben Hayes & Poonam Joshi. Rethinking civic space in an age of intersectional crises: a briefing for funders. Funders Initiative for Civil Society, 2020.

[6] The UN Security Council was the driver behind over 140 governments passing counter terrorism / security laws between 2001 and 2018.

[7] Between 2005 and 2018, over two thirds of communications to the UN Special Rapporteur on Protection and Promotion of Human Rights while Countering Terrorism, related to the use of counterterrorism laws, policies and measures against human rights defenders, civil society groups and activists.

[8] Impact of measures to address terrorism and violent extremism on civic space and the rights of civil society actors and human rights defenders. United Nations, General Assembly (A/HRC/40/52). 2019

[9] Dr Gavin Sullivan and Chris Jones. Is the global counter-terrorism agenda shrinking civic space?. Funders Initiative for Civil Society. 2022

[10] See, for example, members of Seawatch, a German non-profit conducting civil search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean Sea, who have been criminalised for rescuing migrants or offering them legal or humanitarian assistance. Neil Collier, Yousur Al-Hlou and Jacob LaMendola. 65 Migrants Were Picked Up at Sea. Then the Politics Began. The New York Times. 2019.

[11] The Global NPO Coalition on FATF continues to ensure that civil society is effectively engaged in the debate on anti-money-laundering and combatting terrorism financing.

[12] Of particular note is the forthcoming Global Study on the Impact of Counter-Terrorism on Civil Society & Civic Space, produced by the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism. It will be available here from 21 June 2023.

[13] Tawana Petty. Safety vs Security: Are you safe or are you secure? Open Data Bodies, 2019.

[14] Angus Willoughbhy. Biometric Surveillance and the Right to Privacy in IEEE Technology and Society Magazine, vol 36 no 4. 2017

[15] Sarah Chandler and Atifa Qazi. ‘Artificial Intelligence can exacerbate inequality‘ in Kultur Austausch, August 2022.

[16] Cory Doctorow, Nick Buxton and Shaun Matsheza. Seizing the means of computation – how popular movements can topple Big Tech monopolies. Transnational Institute. 2023

[19] The impacts of which were found in this 2022 OHCHR report to have been previously massively underestimated.

[20] More positive examples include the Digital Services Act in the EU; problematic regulations such as the UK ‘Online Safety Bill’ have the potential to violate the right to free expression; legal amendments to the Internet Law in Turkiye had led to Its being dubbed the ‘censorship law’.

[22] As part of Civic Futures FICS funds Intelwatch, a new research and advocacy organisation that has emerged out of long-term research work based at the University of Johannesburg. Intelwatch’s recent report on legal reforms relating to communications surveillance in South Africa has led to them being consulted by the Ministry of Justice.

[23] European Digital Rights (EDRi), supported by the European AI Fund, has led important policy work to advocate on the EU AI regulations.

[24] Arun Kundnani. Abolish National Security. Transnational Institute. 2021.

[25] Arun Kundnani. Abolish National Security. Transnational Institute. 2021.

[26] Laura Thornton. How authoritarians use gender as a weapon. The Washington Post. 2021.

[27] Several efforts are being undertaken to map this ecosystem, including the forthcoming report ‘Weaving Narrative Webs: Understanding the Global Ecosystem for Building Narrative Power’ by the Global Narrative Hive (a new civil society network being incubated by FICS) and a new directory by IRIS – the International Resource for Impact and Storytelling, both due for publication later in 2023.